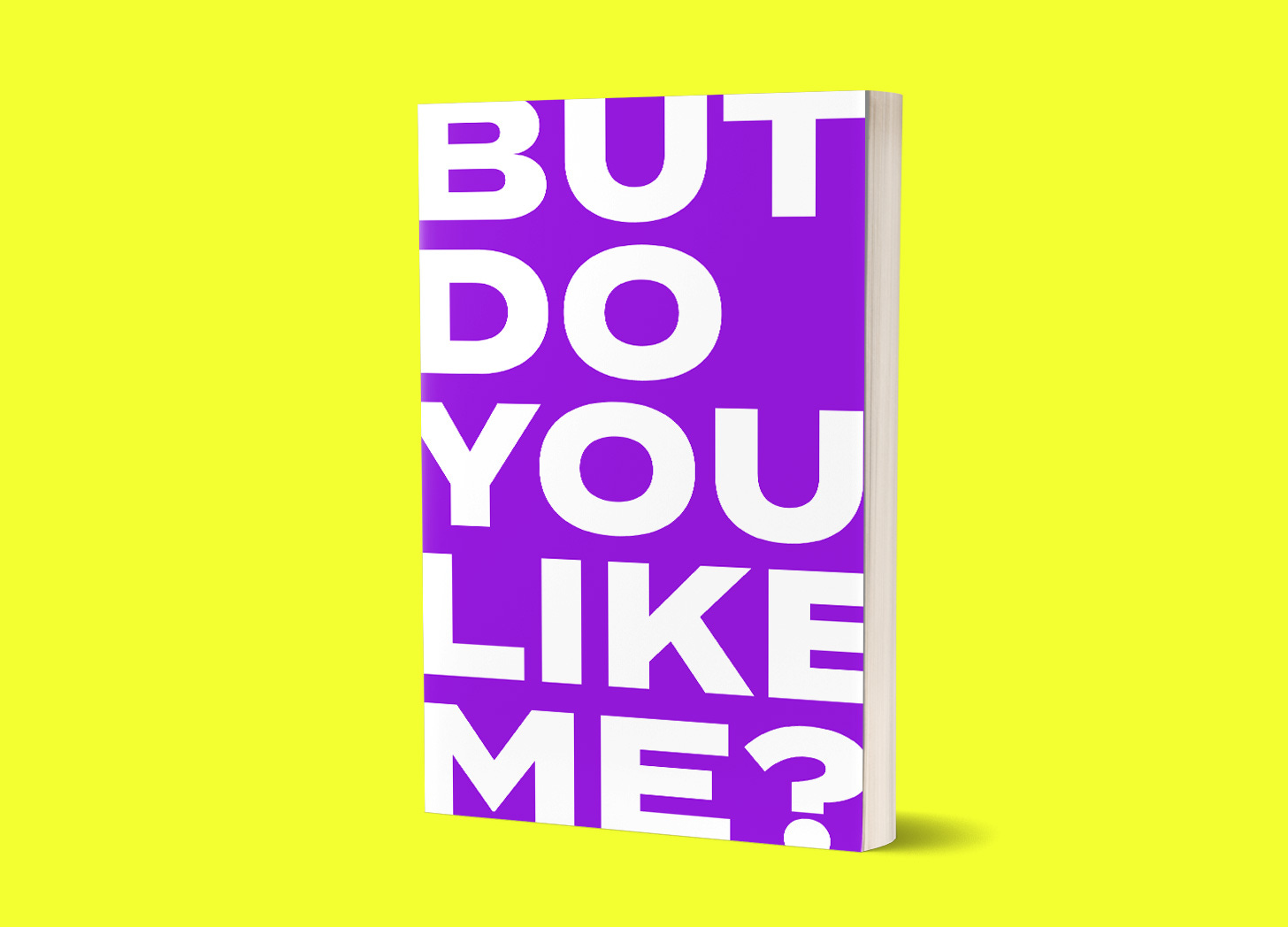

You (Don’t) Need to Like Your Book Cover

Do You?

Hi there,1

Thanks to everyone who filled out my reader survey earlier this week. So far it has been interesting and instructive—you’re a kind and candid bunch and I can’t think of two better things for a person to be. If you missed that missive on Thursday and would still like to tell me off, have no fear: there’s still plenty of time. Just click the button below. Otherwise, on with the show!

Pulitzer-winner Jhumpa Lahiri has a complicated relationship with her book covers.

“A good cover is flattering. I feel myself listened to, understood,” she writes in The Clothing of Books.2 “A bad cover is like an enemy; I find it hateful.

“There is a certain awful cover for one of my books that elicits in me an almost violent response. Every time I am asked to autograph that edition, I feel the impulse to rip the cover off the book.”

Since I reread Lahiri’s essay, this quote and some nagging questions have been rattling around my mind.

Should an author like their book cover? How important is it?

Authors don’t need to like their book cover. It’s not for them.

A book’s cover is not designed for its writer. It’s designed for a potential reader—and buyer. Appealing to the author is not as important as appealing to the reader.

When a book is published, it is no longer the author’s. It is the reader’s.

Authors need to like their book cover. If they don’t, the right reader will also not like it—or pick up the book.

A book cover’s job “is not to attract as many people as possible,” James Hart writes. “It’s to signal to those interested that they would be. It’s a paring down.

“If the author likes the book cover, the cover will very likely be congruent with the story and it’ll draw the right people.”

Authors don’t need to like their book cover. They don’t know what sells.

“[It’s] somewhat important,” says book designer Jordan Wannemacher. “[Authors] don’t know how to best market the book and help it stand out in its category.”

To be read is to be sold.

Authors need to like their book cover. The marketing team cares more about sales than representing the book well.

Left to their own devices, publishers will chase trends and produce copycat covers in the name of sales. At best this is boring and unoriginal; at worst this is harmful and perpetuates stereotypes.

Authors don’t need to like their book cover. The are not taking on the financial risk in publishing the book.

Publishing is a business and it’s naive to think of it otherwise. By investing in an advance against royalties and marketing, the publisher has assumed financial responsibility for the book and should therefore be responsible for decisions about the cover. It’s their money on the line, and the author signed with them of their own volition.

Authors need to like their book cover. Publishers increasingly rely upon authors to market and sell their own books.

“I would have a hard time sharing a book I wrote if didn’t like the cover,” writes Sean Thomas McDonnell. “I’d get sick (quickly) of apologizing for it.”

Today, being published is no guarantee of income, even if there’s a penguin on your spine. A writer needs to be motivated to get their book—and its cover—in front of as many faces as possible.

And even if a publisher does put adequate resources toward selling a book, they are still asking an author to stand by the cover.

“I do think an author must love the cover,” says Amanda Uhle, executive director of McSweeney’s, and author of the forthcoming memoir Destroy This House. “That’s not to say they will design it, and of course some authors want to step all the way back and let the design staff at the publisher take full control. But an author who dislikes their book’s cover is not setting anyone up for success. The publisher is asking the author to stand behind that image, in public, with their heart and soul, hopefully lots of places and times and ways. So they have to love it on some level.”

Authors don’t need to like their book cover. Their aesthetic tastes cannot be trusted.

Without fail, the worst covers I have ever designed are ones over which the author had final say. These authors—in my opinion—often think of the designer as a tool, not a collaborator. This ignores a valuable resource at their disposal.

“In general, I think authors have horrible taste and should not be trusted,” one designer writes. “Some big publishers put out ugly covers, but most of the time they’re better off for excluding author feedback, in my opinion.”

Authors need to like their cover—if they are paying for it.

Even if they have terrible taste. They’re responsible for sales and need to be happy with the book they’ve invested in.

Authors don’t need to like their book cover. They’re too close to their own book to know how it should be represented.

Authors have spent weeks,3 months, or years writing their book. They’re too in the weeds of writing to know how to best represent this thing they have created. If the book is ultimately for readers, then the cover should be determined by the book’s earliest readers and interpreters—the publishing and design team.

Writers sometimes liken their book to a child. Publication represents this child’s entry into adulthood; leaving the nest.4 When a child leaves home, should a parent still tell them how to dress? Do they still know what is best for them?

The above, to quote a term coined by fellow book designer Rae Ganci Hammers, was an intentional exercise in “thoughtful waffling.” There are stances here I agree with more than others, and stances worded far more strongly than I would commit to.

It all has merit. I wanted to give this a clickable, opinionated title without those pesky parentheses, but I couldn’t do it. This was going to be structured as more of a traditional essay, but my waffling was inducing whiplash—if I felt that way, what would it do to a reader? Instead, I wrote this contrarian listicle with some sleep-deprived rambling at the end.

As always, I am a man in the middle of a question. As always, with book design—and life in general, now that I think about it—the answer is “it depends.”

Personally, I lean toward the notion that an author doesn’t need to like their cover, but it is ideal. As a reader first and foremost, my primary allegiance on every cover I design is to the text—but I do want the author to be happy. Unless they have terrible ideas. Unless making the author happy means the publisher fires me. Hmm. Shit.

You can argue with me. I don’t think you’d be wrong! I’ve just been burned by enough authors with both control and bad ideas that I think sometimes an author needs to be saved from themselves. There’s a reason why designer Peter Mendelsund admits we like working on books whose authors are deceased and that “dead authors get the best jackets.”

Speaking of dead authors, here’s Vladimir Nabokov’s sort of bonkers idea for the cover of Lolita:

I want pure colors, melting clouds, accurately drawn details, a sunburst above a receding road with the light reflected in furrows and ruts, after rain. And no girls.5

If Nabokov can’t be trusted with his cover idea, can any writer? I guess your answer may depend on how you feel about Russian literature.

If, like Nabokov, your book is around long enough—and for this to happen it must sell, so congratulations—take heart. It will get a new cover. And you’ll either be rich enough, or dead enough, to not care what it looks like.

I sort of can’t believe this, but I also think that the burden of financial risk is a valid and important factor in who gets to make decisions about a cover.

Unless risk aversion kills a bold, unique cover I have designed. Unless it leads to a safe, trendy design that is actually harmful. Hmmm. Shit.

It’s almost as if publishing is a big, complicated process filled with complex people and companies, none of whom are monoliths with singular identities. Some who—okay, I—may be biased toward a particular outcome for a book cover.

In both my soft, sensitive, personal heart and my hard, (slightly) jaded, professional one, I believe that publishing is at its best when it is collaborative. When compromise happens. That this collaboration is both the biggest frustration and the greatest beauty in the process of publishing a book. No one produces a book alone—and if they do, it’s going to be lacking.

For better (cover) or worse (cover), books are made together.

Extra Quotes

To prepare for this newsletter, I did some informal research and asked what folks thought via social media and email. Here are some more answers I didn’t fit above but still informed my thinking (and waffling). Thanks to all who answered my questions.

I need to like it, not love it. But maybe more, I need to believe it's a good representation of my book, that it works to convey that book to the reader. Of course, if I do love it that's wonderful!

I think the author needs to at least like the cover and feel like it more or less represents what’s in the book. My first book got a cover like this. I didn’t head-over-heels love it, but I liked it, and though it was a little off what I thought the vibe and readership of the book should be, it was close enough. My second cover—while not objectively bad at all—is one that is enough of a mismatch with what I think the book is that I’ve found it actually makes it harder for me to promote. I feel like I’m making excuses for it—”It’s not as light as it looks. It’s not a genre romance.” That’s something no author wants to have to do.

Honestly, I’ve been at this business so long I DNGAF anymore whether the cover appeals to me. Does it appeal to readers? Does it fit market expectations? Does it accurately reflect the “tone” of the book? (comedy, grimdark, romance, etc.). If the design looks wrong to me, the designer better have a good reason for doing what they did - I can be persuaded! And as much as I “write what I want to read” I know that what appeals to me might not sell. I love all the highly decorative vector-art covers in fantasy and romantasy these days, but that won’t work for my paranormal cozy mystery series set in the 1950s.

Which is to say, loving the cover is a nice bonus and does make me more excited to share it, do a cover reveal, etc. but it’s not a deal breaker.”

No matter your client, design is always collaborative. The designer leans on the author for their understanding of the book’s themes and messaging and the author leans on the designer for how to visually communicate those things. If the trust and collaboration exists, than it’s immaterial if the author likes the cover or not, because they know the designer is doing their job regardless.

Like all works of art, you put it out into the world and it’s no longer yours, but it becomes the viewers/readers and that’s kind of what the cover embodies.

At the same time going back to the collaborative process, it is important for a designer to listen to the author and what they’re comfortable with, and how they want the book to be perceived. That becomes a big part of building trust between the designer and author.

I’d say it is essential that authors LIKE the covers of their books. Ideally they LOVE them but there are a lot of factors that can get in the way of that. But a cover that is actually disliked by an author means that it on some level fails to represent their words. And no matter what claim publishers may have to market viability, they are often wrong and/or just speaking from their own taste or from a “that’s the way we do it” mentality. So authors should know there will be compromise but they should feel heard.

Worked in publishing for 15 years. Can't tell you how many times an author has called me in tears, sobbing: the graphic designer chose a random image, and it’s not historically accurate.

The writers feared that readers might judge: if the cover is already inaccurate, then the historical novel is probably not researched accurately.

I've seen authors ending up hating their own book, or not promoting it just because the publisher would not involve them while creating the book cover.

Important, but not necessary.

Covers are often the first impression a reader will have about a book before they decide to buy it, so naturally it's only smart to include a cover's marketability as a primary part of the equation. But I'd argue that many parts of the editorial and production process—not just covers—have some deference to the prospective reader. Ultimately, the book and its cover and other properties have to be appealing in order to reach an audience.

—Amanda Uhle, executive director at McSweeney’s

Great question, and one I think about every project. Ideally, yes! That said, we can only achieve this with clear editorial communication and set expectations.

—Amanda Weiss, book designer

As always, thanks for reading. If you’ve made it this far, I think you absolutely deserve to like your book cover. You clearly have impeccable taste.

If you love this newsletter and want to support it, you can do so by buying me a coffee or becoming a paid subscriber.

Paid subscribers get access to How to Design a Book Cover, a bonus bi-weekly series in which I break down my book cover process from creative brief to final cover. You can read the first post in the series for free here:

Until next time,

—Nathaniel

I’m never quite sure how to start these, even eight months in to this newsletter-writing business. Should I greet you? Just dive right in? “Dear Reader” was pretentious, though I like pretending this is a real letter. Today I went with “hi there” because it’s actually something I awkwardly say when I see someone I sort of know.

This essay also inspired an earlier newsletter of mine: “Book Covers (Don’t) Matter”

If they’re fast as hell.

People often compare publication to birth, but I think entry into adulthood is a more accurate comparison.

FWIW I think his note about “no girls” is a good one.

Art director John Gall on this quote:

I completely agree with Nabokov on what I think is his main point: No little girls. On the other hand, his description of what he would like reads beautifully but would be a complete yawner as a cover. It is so non-specific that it could be the cover of almost any novel ever written. A question I like to ask myself when designing a cover is: “Can this be the cover for any other book?” The closer you get to a “yes,” the worse off you are.

There are two directions for this cover: either you take the title head on and go with some representation of Lolita, or you don’t. But be careful; the land of metaphor is filled with furrows and ruts and roads going off into the distance.

All that being said, I love the concept of ‘pure colors’ as an approach. “Melting clouds?…”

I would never approve a cover to my books (I just finished my third) that I didn’t jibe with.

But then I worked as an art director for 40 years, so I know what works—(not to sound snobbish.)

I loved this article, Nathaniel. The way you wrote it is genius. As an author and publisher of my books, I need the cover to appeal to people I hope will love the book. And I need to love it. I’m starting work today with my book designers, and I confess, I am scared. It’s a big process and while I trust them completely, I don’t know exactly what I want. I go back to the first cover they designed for me. I would never have imagined what they came up with. I insisted that there would be NO Eiffel Tower on the cover. (I hate clichés.) But in the end, there it was, albeit at an angle. I love the cover. (Chasing Sylvia Beach, if you want to check it out.) I have some ideas for the new one, and plan to go to the bookstore today for research and to gain some language around what I am feeling for the cover. I need to love it, because I need to have that buoyant feeling when I share the book, pass out postcards, etc. Your articles are helping me think more about book covers and I appreciate the work you do and how you write about it.