A Public Library’s Publishing Imprint

A Look Inside Ann Arbor District Library's Fifth Avenue Press

Earlier this year, The Los Angeles Public Library made headlines when it was announced the library had acquired Angel City Press, the 30-year-old independent L.A. publisher. It’s an exciting development, and one that, in my opinion, makes complete sense. But then again, I’ve been designing books for a library publisher for the last five years.

The Los Angeles Public Library isn’t the first library with a publishing arm—and I’m not talking about NYPL or the Library of Congress. Since 2017, The Ann Arbor District Library has published more than 50 books under its publishing imprint Fifth Avenue Press. “Locally focused and publicly owned,” Fifth Avenue Press was created to support the Ann Arbor writing community and promote the creation of original content that might not otherwise exist. As far as I know, there is not another publishing model like this in the country (but please, tell me if I am wrong!).

How it Works

These days, books are typically published in a few standard models.

Traditional publishing: A publisher—say, Penguin Random House—pays the author an advance against royalties, and fronts all of the production and marketing costs (eh, sorta). The author must “outearn” their advance before receiving royalties on their book, at a rate which was agreed upon in their contract.

Self-publishing: The author produces and sells their book themselves. Costs are theirs, but so are profits. Platforms like Amazon KDP and Ingram Spark provide avenues for the self-published authors to print and distribute their books with little, if any, up-front costs.

Hybrid Publishing: A newer model, once derisively thought of as “vanity publishing,” hybrid publishing is just that: a hybrid between traditional and self-publishing. In this model, an author shares the cost of the book making (sometimes to the tune of several tens of thousands of dollars), but in turn receive professional design, editing, sometimes ghostwriting, and a much larger royalty rate.

Fifth Avenue Press doesn’t fit neatly into any of these categories. If anything, it’s closest to the hybrid model—but perhaps even more of a hybrid between traditional and self-publishing. Let me explain.

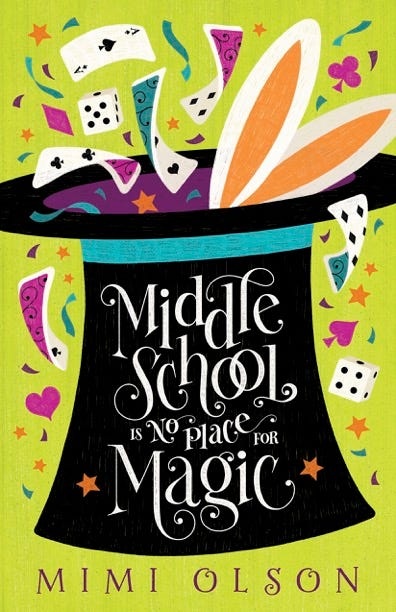

Like a traditional publisher, Fifth Avenue Press authors do not pay for design or editorial services. However, like self-publishing, they are responsible for any print and marketing costs for their book. Fifth Avenue Press does not pay advances against royalties, but it also has no commercial stake in publishing—all profits go to the author. Like a traditional publisher, Fifth Avenue Press does not accept every book submitted. Prospective authors must reside in Washtenaw County, or their book must be about something in the area. Submitted books are subjected to review and only about 20% of submissions are published.

The only “compensation” Fifth Avenue Press and AADL asks for is the ability to put PDFs of the book in the digital collection for library patrons to download. Additionally, the library purchases 11 physical copies of the books. Each year, at the A2 Community Bookfest (formerly Kerrytown Book Fest), the press has an event celebrating the releases from the past season. Here, the authors may read from and sell their books to the community.

Fifth Avenue Press continues to grow and change every year. In 2023, it co-published Cinema Ann Arbor, an illustrated coffee table book about student film societies, with University of Michigan Press. It was shortlisted for the 2023 Alice Award and named a 2024 Michigan Notable Book. I had the immense pleasure of working on this book.

What if?

Now, I’m biased. I work for the Ann Arbor District Library and design books for Fifth Avenue Press. But even if I didn’t, I would think it is an incredible program. What would the world look like if more public libraries had the money to run “locally focused and publicly owned” publishing imprints?

Hub City Press in Spartanburg, SC, has a t-shirt that says “decentralize publishing” that I think about a lot (I still need to buy one). The longer I do this book design thing, the more interested I am in that decentralization. The ever-homogenizing output of the Big 5 means that local interest books and writers are increasingly relegated to the fringe in favor of what sells. And to that point, what sells is increasingly narrowing! What if local books were produced by local libraries? What if there were more non-profit, hybrid models whose work wasn’t predicated on selling, but on producing professional, diverse, and interesting work, important to the communities in which it is produced?

I think Fifth Avenue Press is special and unique, but it doesn’t have to be.

I wasn’t aware of this! Such a cool model.